This article was written by Ruby Hinchliffe and Alex Davenport

New Centrist Party Emerges

by Ruby Hinchliffe

It has been revealed by The Observer that a new centrist party is emerging. Its year-long existence has been kept under wraps, until now, as we hear that the party has received £50 million in funding. Most of this backing has come from the multi-millionaire Simon Franks, the founder of LoveFilm and former Labour benefactor, who is ‘leading’ the party in its embryonic stages. The party is yet to have any official political backers, and has not yet received an official name.

Their tagline announces that they will “break the Westminster mould”, offering the most striking challenge so far to the current tribal nature of politics, which limits voters to just two mainstream parties: the Conservatives and Labour.

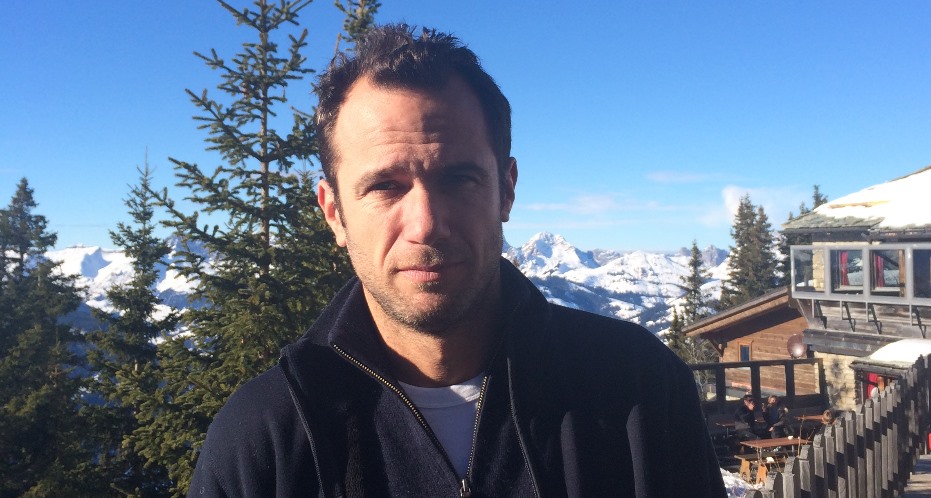

Founder of the as yet unnamed centrist party, Simon Franks (Source: Asia House)

Founder of the as yet unnamed centrist party, Simon Franks (Source: Asia House)

The once-upon-a-time ‘centrist’ Liberal Democrats have practically disappeared now, winning just 12 seats in the last election. This lack of a third party option, paired with the polarisation of Britain following the Brexit referendum vote, has led us to a vast divide on the political spectrum. Indeed, former Liberal Democrat leader and deputy prime minister Nick Clegg has said the formation of a centrist party is “highly likely”.

In Westminster, we have seen moderate Labour MPs become disassociated with their party since the return of the hard left under Jeremy Corbyn. We have also seen the alienation of more modern, pro-European Tories, by the Conservatives’ ‘Hard Brexit’ stance, and the recent rise of traditional Tory MPs such as Jacob Rees-Mogg.

An appetite for party alternatives is becoming apparent, and it stretches further than just parliament. The National Centre for Social Research found that, on average, more than 56% of the British public do not feel as though any mainstream political party represents the views of people like them.

So, what does a centrist party look like, and what stance has this particular centrist party decided to take?

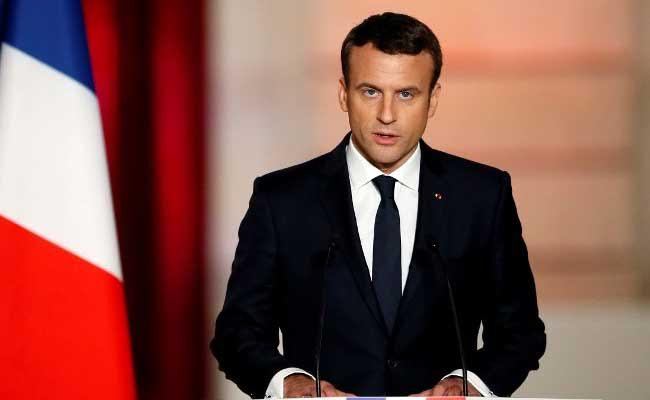

The idea of a centrist position is that it draws from both right and left politics. Emmanuel Macron, the French president, made a successful ‘centrist snatch’ last year, and is now 11 months into his presidency. His policies aim to establish France as more business-friendly and self-sufficient, but they also aim to deconstruct the “French social model” that leads young people and ethnic minorities into historically high unemployment. His ideology prioritises both economic and social issues.

French President Emmanuel Macron (Source: NDTV)

French President Emmanuel Macron (Source: NDTV)

In the UK, the Conservatives are far more orientated towards the economy, just as Labour are far more oriented towards social justice. There is little room for compromise.

This new centrist party has been defined by the following stances in The Observer:

- Higher taxes on the rich

- Tighter controls on immigration

- More funding to the NHS

- Improved social mobility

- A focus on wealth creation and entrepreneurship

- All potential candidates to sign strict term limits, preventing MPs from remaining safe in their seats for decades

- It has also been said by one source that Brexit supporters are involved with the party

Their stances suggest that they are playing to a more centre-left audience. There seems to be a consensus that future candidates for the party will run in the 2022 election, and that the party will be formerly established later this year.

Those hoping for a new centrist party in Britain shouldn’t hold their breath

by Alex Davenport

On the surface, it seems like there is potential for this as yet nameless centrist party to make inroads into British politics. Indeed, some polling may suggest there is a demand among voters for a new party in the centre ground. A ComRes poll on the eve of last year’s general election found that 45% of respondents were in favour of the idea of a new centre party being formed. Meanwhile surveys consistently show both Jeremy Corbyn and Theresa May languishing in the negatives with regard to approval ratings. It seems intuitive that with Labour and the Conservatives moving ideologically further apart, each with an unpopular leader at the helm, would be the best time for a party to spring up in between them and win voters from both.

This is why we need a centre party. May's only opposition is against a nobody, with no party, no policy and no funds but they are still beating Jeremy Corbyn by 9 points. It is time to fill the gap. pic.twitter.com/8ay2Vxc29J

— grumpyinbolton (@grumpyinbolton) April 9, 2018

The party could also take confidence from the success of Emmanuel Macron and his République En Marche (REM) party in France. The newly-formed liberal party led by Macron, a former cabinet minister for the Socialist Party, won both the presidency and a substantial majority in the French legislature. Much of their success was founded upon the electoral coalition they built, uniting young, liberal-minded voters and more affluent members of the middle class with their mix of socially progressive and economically pro-free market policies. This is the kind of broad appeal the British centrist party will hope to have when it starts putting candidates forward.

Yet there are several serious hurdles for this new party to overcome if it is to have success comparable in any way to Macron and REM. For one, the British electoral system makes it particularly hard for new parties to succeed. Our ‘first-past-the-post’ system is arranged so that whichever party wins the most votes in a particular seat automatically wins the seat, regardless of how much they win by or by how popular the party is outside the seat in question. This means that a party needs to build up a strong concentration of voters in specific regions to stand a chance of winning seats. A party that receives, say, 20% of the vote across the country may in theory not win a single seat if its support is distributed so equally across the country that it does not translate into success is any one constituency.

It seems unlikely that Franks’ centrist party would be able to – out of nowhere – win such strongly localised support bases that they genuinely challenge Labour and the Tories in specific seats, and would instead be likely to suffer at best a series of unhelpful second- and third-placed finishes with precious few actual victories to their name. Critics of Franks’ project point to the Social Democratic Party of the 1980s as an example of this: when four senior Labour politicians broke away from the party to form a liberal alliance, they took only 23 seats despite netting millions of votes in 1983’s general election.

New Centre Party? Seen this film before. Remember how it ended? 18 years of Tory government and the SDP being wound up after it received less votes than the Monster Raving Loony Party in the Bootle by-election. https://t.co/Eumpx2a46w

— Chris Mullin (@chrismullinexmp) April 9, 2018

Also, the evidence that there really is demand for a centre party is somewhat dubious. While polls may suggest that voters think it is a good idea to have a centre party, sometimes it is better to go on what people do than what they say. At the 2017 election, the proportion of voters supporting one of the two main parties was at its highest in a generation, with Labour and the Conservatives’ combined share of the vote reaching 82%. The main centrist alternative, the Liberal Democrats, won only 7.4% in comparison. Seen in this way, the British public do not seem desperate for alternatives to the two main parties, including those in the centre ground.

The ‘Lib Dem fightback’ failed to materialise for Tim Farron’s party in 2017 (Source: BBC)

The ‘Lib Dem fightback’ failed to materialise for Tim Farron’s party in 2017 (Source: BBC)

This is not to say that Franks’ party is doomed to fail. If politics has taught us anything over the past few years, it is that we should never be too bold in our predictions. It is not beyond the realms of possibility that a new party could change the status quo in one way or another. Even if this new party struggles to win any seats, it may succeed in setting the agenda and dominating the discussion on certain issues, as UKIP did so effectively on immigration and the European Union. Yet posing a genuine challenge to the big beasts of British politics is easier said than done.